Published by Cybersecurity Practice

September 6, 2023

t: 0333 666 5777e: hello@itgl.com

ITGL Limited, Trafalgar House,

223 Southampton Road,

Portsmouth, PO6 4PY

You would be forgiven for thinking that cloud security failures are something of an inevitability in this day and age. On any given day, you can find news stories of attacks and breaches upon cloud providers of all sizes, up to and including the big hitters like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google. Given that the vast majority of organisations are using at least one cloud environment (or more likely, as a recent State of the Cloud report from Pluralsight indicates, multiple), it’s no wonder that some CISOs are beginning to view cloud services more as potential liabilities than assets.

It’s important to start off by noting that the use of cloud services does not innately present a security threat. Rather, the issues that surround them primarily stem from misunderstandings and misconfigurations on the part of the organisation deploying them. In fact, Gartner’s 2019 report ‘Is the cloud secure?’ predicts that “through 2025, 99% of cloud security failures will be the customer’s fault” – a claim echoed by Check Point Software’s 2023 Cloud Security Report, which ranks misconfiguration or improper setup as the most significant threat to cloud security.

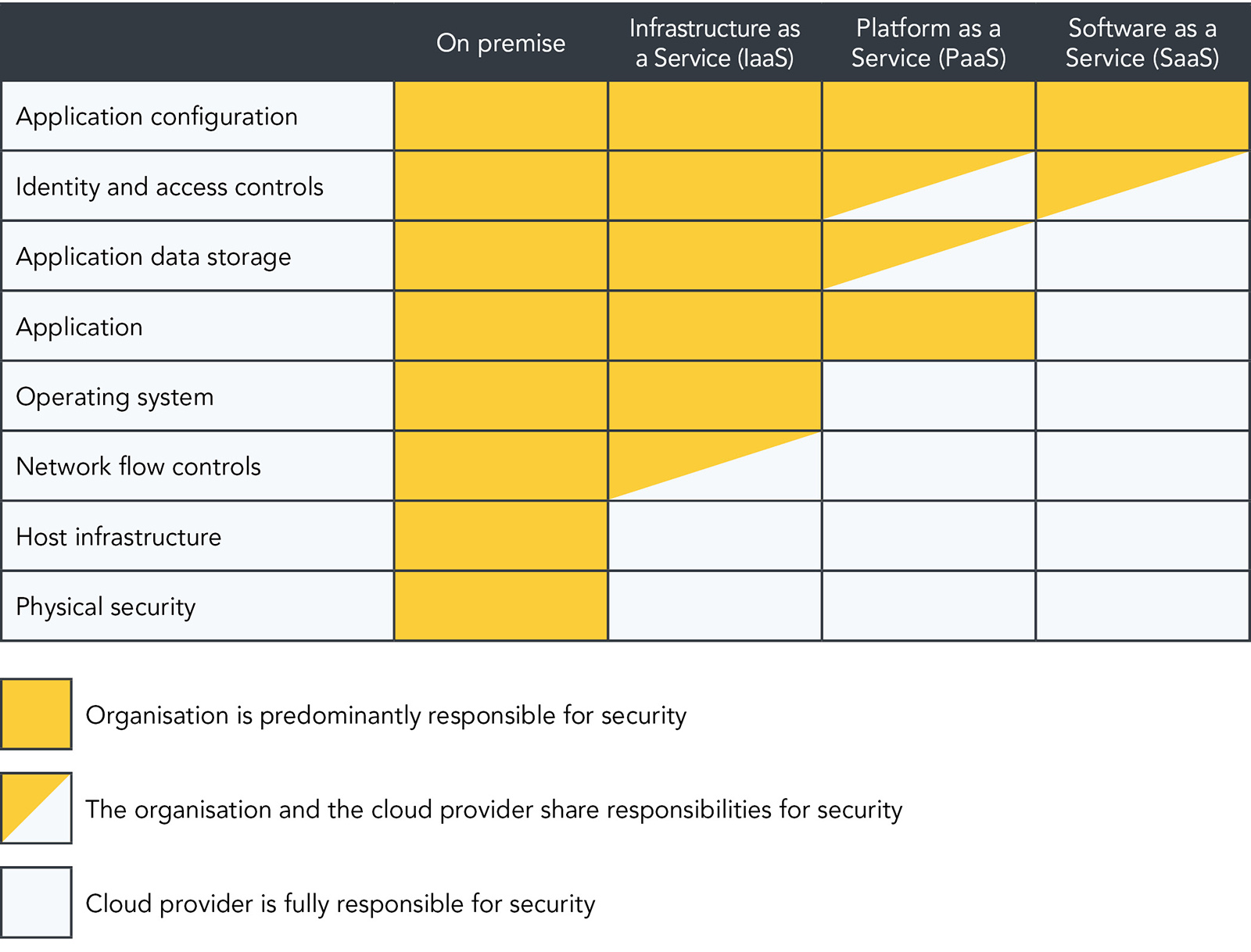

It’s a not-uncommon presumption amongst organisations employing the services of a cloud vendor for the first time that, by doing so, they are effectively relinquishing responsibility for the security of the systems and data deployed on the cloud. In reality, responsibility is effectively split between the organisation and the cloud provider. The extent to which each takes responsibility varies depending on the services at play (see the table below), but there are no situations where the organisation is totally absolved of its responsibilities across the board. Even in the instance of Software as a Service (SaaS), while the cloud provider is responsible for the security of the physical infrastructure, operating system, application, and data storage, the organisation remains responsible for the security of the application configuration, and shares responsibility of identity and access controls.

It’s instances such as these – where the organisation isn’t clear on where its responsibilities end, or how to correctly set up its cloud environments – that can create dangerous grey areas and blind spots in an organisation’s cloud security. And it’s these situations that give rise to most of the news stories around breaches and effective attacks on cloud services.

Of course, for many organisations, awareness won’t be the issue. Even in situations where the internal IT team is keenly aware of their responsibilities, there remain the perennial issues of tight resources and understaffing. In Permiso’s 2023 Cloud Detection and Response Survey, 95% of the 500+ security, engineering, and IT professionals surveyed expressed concern that their current tools and teams may not be able to detect and respond to a security event in their cloud environments. With many teams already wrestling to maintain security over the systems and devices within their physical estate, effectively monitoring and maintaining cloud security may simply be beyond organisational bandwidth for many.

The good news is that there’s a reasonable amount of consensus around concrete actions to be taken to help secure cloud architecture. A foundational first step is to develop a zero trust framework that extends across all organisational systems and resources – cloud based or not. Such a step will require substantial investment, but can improve the security posture of the organisation more effectively than any other single suggestion.

A less involved approach is to work towards implementing deep observability within the organisation’s systems. Real-time network-level intelligence can be combined with traditional metrics and logs to help the organisation to monitor traffic moving laterally between systems, rather than just traffic moving between internal and external sources. At the same time, it can be used to identify potential ransomware that might be hidden within a hybrid or multi-cloud environment.

Another positive step is to cut down on as much as is possible on shadow data present within the organisation. That is, data held by the organisation that is copied, backed up, or stored within an unmonitored or ungoverned data store. This data is by its nature much more likely to be held in an insecure or misconfigured manner that does not meet the organisation’s general policies for data storage. Having the stringent asset management necessary to cut down on such data will necessarily produce a comprehensive map of all organisational data and its location, giving a clear picture of exactly what data is stored in the cloud, and whether such storage is even still needed.

Finally, asking an expert to review – or, ideally, set up – your cloud configurations will drastically reduce the risk of misconfigurations that could be exploited by bad actors. The NCSC has put together a summary of 14 cloud security principles that can help organisations select a cloud provider that meets their security needs, but it remains up to the organisation to consider how to securely configure these services.

Of course, none of this will protect an organisation against the purported ‘1%’ of cloud security failures that can be blamed on the provider – as with everything in cyber security, there are no absolutes. Nevertheless, an organisation that is fully abreast of their cloud services, their data held within them, and their responsibilities regarding it, will be far more protected than otherwise. If you’re left unsure of any of the approaches mentioned here, or would like to discuss the most effective way forward for your organisation specifically, we can help. Get in touch at security@itgl.com to start the conversation.